DESIGNS

Ottoman mosques developed with the empire’s expansion, starting as simple structures before becoming more elaborate, innovative and spacious for the faithful. Smaller mosques featured a single minaret that could be typically found on the right side of the building’s entrance.

Bigger, more lavish imperial mosques can have up to six minarets that can arise from all four corners of the mosque and courtyard – as with the case of Sultan Ahmet I Camii. These same minarets often have balconies that are elaborately decorated from which the call to prayer, or ezan, is given by the muezzin.

With the construction of bigger mosques, Ottoman architects in the 15th century began looking for methods to support large spaces with as few vertical columns as possible.

This was to give the faithful more room to pray and as mentioned before, to exemplify their wealth and power.

In addition, space syntax research and testing have proved that human, or worshipper, behaviour can be influenced by the spatial arrangements in a building’s layout.

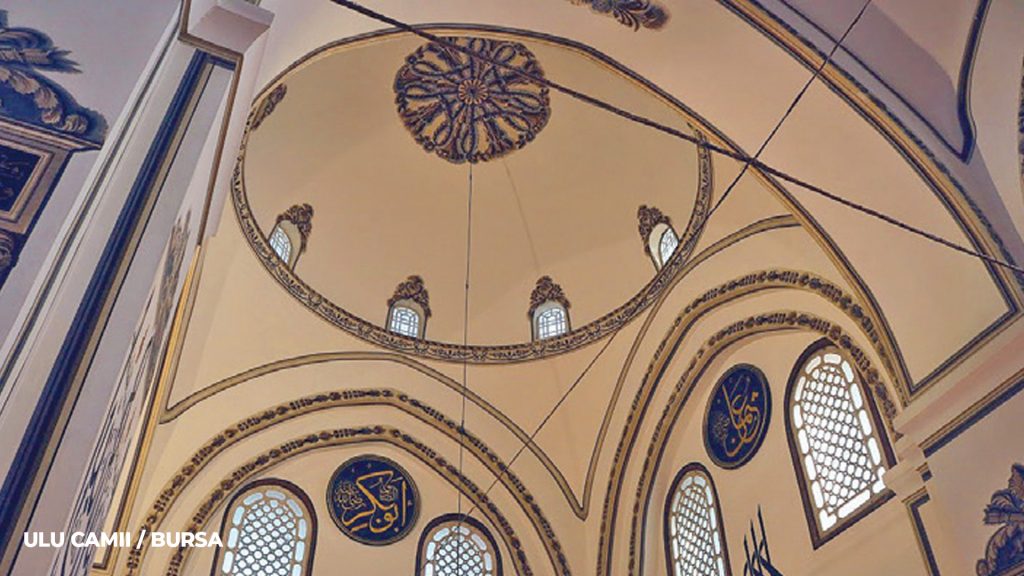

The process of building mosques with less vertical supports was achieved in stages. The first stage involved veering away from the seljuk custom of placing a single dome in front of the mihrab or alternatively, placing a row of three domes for special effects. The Ulu Camii, or the Grand Mosque of Bursa is an example of this.

In the second stage of eliminating fewer columns, a larger dome was constructed at the hall’s centre. Edirne’s Uc Serefeli Mosque is an example of this method. In the final stage, the smaller bays that surrounded the large central area were integrated under half domes on up to four sides of the space. A classic example of this is the Bayezid Camii in Istanbul.

FUNCTIONS

Large mosques typically feature a monumental courtyard, called the avlu, which is surrounded by a domed arcade and has a big gateway opposite the main entrance to the mosque. In the centre of the courtyard there is almost always an ablution fountain, or sadirvan, where people perform ritual washings, also called abdest, before praying.

The interior furnishings of all Ottoman mosques are the same. One distinct feature that is the most important element in any mosque is the mihrab, a recess centred in the wall opposite the main doorway indicating the direction of the qibla. The mihrab is generally produced from finely carved marble.

The imperial mosques always have an loge, or hunkar mahfili, which is a separate chamber screened off by a grille to shield the sultan and his party from the public gaze when they attended services. This royal enclosure was usually located in the left corner of the gallery facing the mihrab, and oftentimes had its own entrance.

GARDENS

“A similitude of the Garden which those who keep their duty (to God) are promised: Therein are rivers of water unpolluted, and rivers of milk whereof the flavour changes not, and rivers of wine delicious to the drinkers, and rivers of clear-run honey; therein for them is every kind of fruit, with pardon from their Lord’.(47:15)

Gardens in the Ottoman period were strongly impacted by Quranic descriptions of paradise, therefore they reflected spaces with abstract notions of heaven, symbolizing serene areas that demonstrated ‘eternity and peace’.

As it was common for Ottoman mosques to have adjacent gardens, it was no surprise that some mosque structures were built in relation to their gardens. For example, to create continuity with its garden, the Suleymaniye Mosque has windows in the qibla wall while its mihrab has Iznik tiles and stained glass windows that symbolize a gateway to paradise.

Many decorative patterns in architectural details and even urban structure were inspired by nature.

This was not just limited to the ceilings of mosques, but was also extended to palace walls, pavilions, kiosks and more. The most prominent method of embellishing structures was through Turkish tiling, the most interesting technique being the cuerda seca where the tile’s glazes were coloured instead of the more common method of having a painted glaze covering a painted design.

The colours, as they were painted directly onto the glaze, were prevented from running into each other by a thin dividing line.

These beautiful tiles are very rare in Istanbul. The best examples can be found in Prince Mehmet’s turbe at Sehzade Camii and Cinili Kosk’s porch, Topkapi Sarayi’s oldest extant building.